By Erica D. Pratt, Ph.D.

As a graduate student at Cornell University in the 2010s, I was highly motivated to become a tenure-track (TT) professor at a research-intensive university. However, I had little understanding of how the components of a faculty application were evaluated and ranked to create a short-list of prospective candidates. Luckily, my field department realized that providing their trainees insight into the hiring process was critical to our future success. I was given the opportunity to serve on multiple student ad hoc committees for TT faculty searches. Candidates agreed to allow graduate students and postdocs to review their application materials (CV, research and teaching statements). Our committees reviewed a subset of candidates’ written materials, interviewed candidates brought on-campus, and attended their open and closed session presentations. We made final hiring recommendations which were taken in an advisory capacity by the ongoing search committees.

As a graduate student at Cornell University in the 2010s, I was highly motivated to become a tenure-track (TT) professor at a research-intensive university. However, I had little understanding of how the components of a faculty application were evaluated and ranked to create a short-list of prospective candidates. Luckily, my field department realized that providing their trainees insight into the hiring process was critical to our future success. I was given the opportunity to serve on multiple student ad hoc committees for TT faculty searches. Candidates agreed to allow graduate students and postdocs to review their application materials (CV, research and teaching statements). Our committees reviewed a subset of candidates’ written materials, interviewed candidates brought on-campus, and attended their open and closed session presentations. We made final hiring recommendations which were taken in an advisory capacity by the ongoing search committees.

Many trainees never have this kind of opportunity; and, I decided sharing what we learned about the faculty interview process could provide insight to the TT hiring criteria at a "research 1" (R1) institution. I developed the following rubric for the committee that I had co-chaired (generated independently of the internal faculty evaluation forms) to score candidates based on written materials and interviews. Our rating system was as follows: Excellent (E), Very Good (VG), Good (G), Fair (F), and Poor (P).

The rest of this article will discuss things that we found differentiating for candidates in each category:

Awards: We noted awards of fellowships, patents, travel grants, etc.; but, availability and competitiveness is often very field-specific. We found this category was not as differentiating between candidates as we had anticipated.

Collaborations: Candidates ranked highly in this category had previously established collaborations often outside their home institutions. They explicitly pointed out potential collaborations in programs/cores at our institution or listed faculty that they had already approached about future collaborations. Our anticipation of areas for synergy in the research proposal was good; but, the candidate clearly pointing them out was even better.

Impact: The most impactful research statements placed a heavy emphasis on contextualizing their work and describing how it improved on the current state of the art. In my opinion, this is an area especially emphasized for engineering disciplines. An "E "rating meant the application successfully walked the line between being precise enough to convince colleagues of the candidate’s expertise but general enough for non-specialists to understand and appreciate. To us, this demonstrated the candidate had an excellent long- and short-term vision in their field.

Management: Here, we looked for a clear vision on building a lab, prioritizing projects, and acquisition of different types of trainees. Cornell is liberal with field appointments in other departments and allows recruitment of graduate students across said departments. Hence, highly ranked candidates knew what types of engineers they required for different projects, and designed said projects so that they would intellectually engage the students working on them. Top candidates had clear short- (1st year), mid-(5 year), and long-term project (post-tenure) planning goals.

Mentorship: In applications, listing experience at managing junior trainees was important. In interviews, we looked for clear expectations on productivity via papers, conferences, presentations, etc. We asked for descriptions on how outlined projects would be carved into reasonably sized, PhD-level, chunks. Highly-rated candidates knew what skillsets their students should have by the time they left the lab. Many engineering PhDs go into industry, so having a concise answer of how to mentor, and provide opportunities for, such students (despite perhaps never having worked in industry) was non-trivial.

Ownership of Work: This one is intuitive. Top-ranked candidates clearly delineated gaps in the field that they were uniquely qualified to fill and proposed a research program which capitalized on it. In doing so, they differentiated themselves from their PhD and postdoctoral advisors.

Past Funding: Candidates who had obtained prior independent grants received the highest ratings. Assisting their past supervisors in successful grant applications was also well received.

Proposed Funding: Top-ranked candidates actively identified directorates and active funding calls to which they could apply. Many of these agencies were ones where they had previously received funding while postdocs or graduate students. Their portfolios were diverse, both in terms of federal versus non-federal funding agencies, as well as total award amount.

Productivity: Unfortunately, there is no magic number here. We tried to balance number of papers with journal impact, author placement, and rate of publishing. I recently went back to look at the publishing rates for all the faculty candidate seminars I had attended during my Ph.D.; and, the average number of first author publications was 8 (ranging from 2 to 14).

Research Feasibility: This was usually related to the ownership of work category. If the candidate was able to clearly identify a unique niche for their research program, it usually built on skillsets that they had developed in their graduate and post-graduate training. Proposing an entirely new research direction here usually meant the candidate had not achieved separation from their PhD and postdoctoral mentors.

Teaching: Most engineering departments at Cornell do not have a separate teaching seminar so the quality of teaching statement and research seminar presentations were really important. Successful candidates identified core classes at Cornell that they were qualified to teach; and, cnadidates also proposed new courses that were unique and non-overlapping with existing offerings. Finding up-to-date course offerings can be challenging, so my best suggestion would be to contact the department's administration ahead of time. The best presenters used minimal jargon and explained field-specific terms clearly and succinctly.

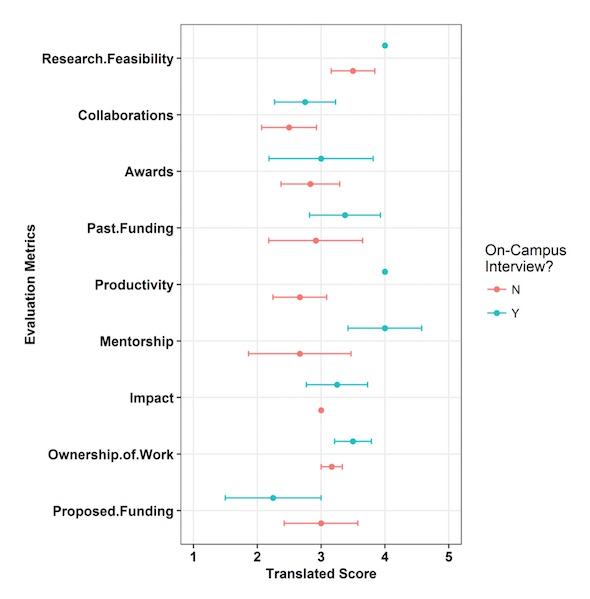

Overall, I think the qualities that made candidates stand out are unsurprising. However, it was a very informative experience for me to see what worked, didn't work, and what factors most strongly influenced our evaluation of a candidate. Candidates who were selected for on-campus interviews were highly-rated in most categories (see figure below); but, there was no one factor that clearly distinguished between the two groups. I think the most important quality, which we realized in retrospect, was the ability to communicate powerfully and succinctly while providing context for the scientific questions candidates were trying to answer. Most people, outside the search committee, did not read any of the candidates' papers (sorry!) so these abilities were critical.

In closing, I would like to thank the Sibley School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering at Cornell for giving me the opportunity to sit on these ad hoc committees especially as a graduate student! I would also like to thank the candidates for trusting us to be conscientious with their application documents. It was an amazing and informative experience, and is something I think more institutions should consider for their graduate trainees and postdoctoral fellows.

Figure: Evaluation range of assessed faculty candidates. The scoring rubric Excellent through Poor criteria was translated to a 5 to 1 score for each category. The mean and distribution of candidates are shown for candidates invited for an on-campus interview (blue) and all candidates evaluated (red).

E.D. Pratt (2019) Observations on the Tenure-Track Faculty Application Process. DiverseScholar 10:3

Erica D. Pratt, Ph.D. is currently a postdoctoral fellow in Biochemistry at the University of Minnesota-Twin Cities. Her work focuses on the design of liquid biopsy-based assays for the early detection of pancreatic cancer. Any opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author.

DiverseScholar is now publishing original written works. Submit article ideas by contacting us at info@DiverseScholar.org. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 Unported License.

Originally published 29-Dec-2019